China's Infrastructure Push: Old Habits Die Hard

In the excitement in the re-opening after covid-19, expectations have been high for a strong rebound in China’s economy.

So far, the evidence has been mixed. In part it reflects limited detailed data at the turn of the year (data tends to lump January and February together due to Chinese New Year distortions). But it can also mean that a recovery is just going to take longer than anticipated.

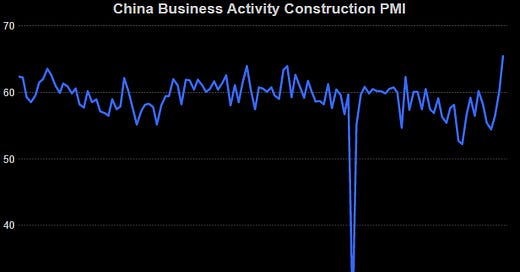

Last week, there were some more tentative signs of a pickup in economic activity – notably in infrastructure and construction. An index measuring construction activity has lifted to its highest since at least 2012 – see chart below:

State media have also done its part in promoting the image that China is back – headlining an estimated 10% increase in infrastructure spending in the first quarter on a year ago.

Provinces are declaring new major projects in transport, water conservation, advanced manufacturing, modern services and new types of infrastructure. China’s State Railway have also passed on data to State media declaring a 6.6% increase in fixed-asset investment in railways.

So, there are big pats on the back for all involved in doing their part for the economy and helping to meet the 5% growth target.

Of course, there is one big glaring problem here.

The recovery from covid-19 was expected to drive a rebound in household and private business spending, which were hit the hardest by the lockdowns. It was the so-called “quality growth” that would be able to drive the recovery.

By setting what seemed to be a conservative growth target of 5% for 2023, it implied that authorities wouldn’t have to resort to building unproductive and unprofitable projects. Because households and the rest of the private sector, would be back after covid lockdowns were lifted.

So, it may be puzzling why there would be a new infrastructure binge. Could this mean that authorities are worried that any recovery in the private sector will not be enough to meet the 5% growth target?

Possibly. At first glance this may seem like the case.

But this is not necessarily so. It is probably more to do with what the growth target signifies in China. The growth target gives the greenlight for local governments and SOEs to do what they have done in the past few decades or so. And that is to find ways to spend on projects so it can add to GDP growth and meet the CCP goals.

There is also an added aim and that is to find 12 million jobs this year, which building projects helps to achieve.

It is more a case of authorities doing what they have always done – if they feel that the economy needs support, infrastructure continues to be favoured as the main growth driver, which in turn supports employment and therefore drive consumption indirectly.

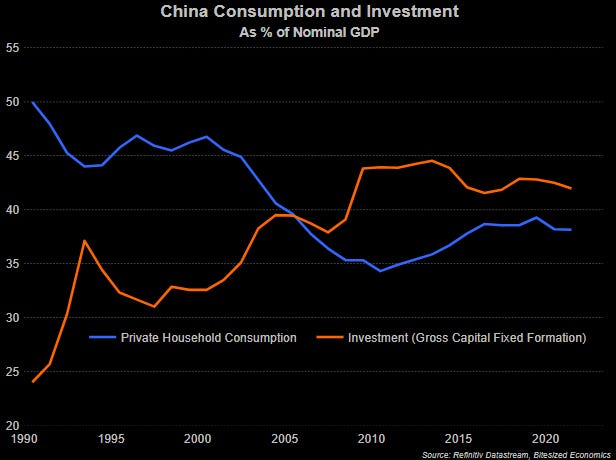

For many years now, there has been a concern about growth being too driven by investment, and not enough by consumption. This rebalancing that is necessary for more sustainable growth is well known among key officials.

But as much as key officials know that they want more economic growth to come from consumption and are aware of a need for rebalancing, policies do not seem to be shifting down this path.

Why might this be the case?

The big reason is because of what rebalancing actually entails. The easiest and fastest way to rebalance would essentially mean that investment contracts, and that would mean that the economy may need to stagnate or even contract. A growth target of 5%, or any growth target for that matter this year, would be difficult to achieve without an infrastructure push.

Now that investment comprises such a large proportion of China’s economy, there is also a dependency on it for supporting other aspects of the economy, including the household sector. Say if there were to be a contraction in investment, that would help to re-balance, but would also surely bring about a contraction in incomes and therefore consumption.

But another possible reason for why rebalancing the economy towards the consumer is not happening is a more ideological one. In some other places in the world, one solution might seem obvious – just provide handouts to households instead of building infrastructure. After all, that is what nearly every advanced economy did to get out of their covid-induced slumps. It isn’t exactly clear why there seems to be such an unwillingness against providing significant stimulus directly to consumers. Perhaps it goes against the 60’s image of the ideal Chinese hardworking labourer. Or perhaps vested interests don’t want more stimulus directly to households would mean less funding to them.

Basically, China’s institutions and political structure has been built around an investment-led growth model, which worked well 20 years ago, but not so much today.

For now, the infrastructure push which will translate to ongoing demand for steel, iron ore and base metals, is to continue while China aims for its growth target this year. Indeed, any growth target of at least 3% in the foreseeable future would likely imply ongoing reliance on investment spending unless greater transfers go directly to households.

That does not mean however, that household spending and the private sector won’t grow as much as expected this year. It is just that kickstarting this part of the economy will need to come indirectly – from investment and the spending by the State sector. And a recovery in these parts of the economy will take longer than if more stimulus was given directly to them, as in other parts of the world.

This might all seem like the problem of debt and reliance on investment is the can being kicked down the road for now. At least until the government knows that this year’s growth target will be met.

******************************************************************************

Thank you all for your support and reading this newsletter.

If you like what you are reading, you can subscribe here:

Alternatively, you can also show your support through my buy me a coffee link available here:

https://buymeacoffee.com/januchanD