Making sense of China’s GDP

In Hong Kong, where I have lived for the last three to four years, there has no doubt been a huge amount of change since moving here in the middle of the pandemic.

Today, the streets are now once again bustling. The MTR, Hong Kong’s underground railway is crammed with people. Queues pop up outside the new hottest restaurant or other attractions.

Tourists are coming back too – visitor arrivals in the first two months of the year were up almost threefold on a year ago according to the Hong Kong Tourism Board. And almost 80% of those tourists came from the Mainland.

But there are some tell-tale signs that visitors from the Mainland are a different kind of tourist in comparison to before the pandemic. While they have come back, gone are the queues outside Louis Vuitton and Gucci. The crowds at high-end shopping malls also never came back. Instead, you can see buses filled with tourists at Repulse Bay, one of Hong Kong’s main beaches, or the younger crowd flocking to Kennedy Town to take selfies.

The Chinese consumer is not spending like it used to.

Indeed, in recent economic data there was further evidence of a sluggish consumer as retail spending slowed to just 3.1% in the year to March from 5.5% in February.

Yet, Chinese GDP grew an annual 5.3% in the first quarter. This was a surprisingly strong result given some of the challenges that China has been facing and beat expectations of 4.6%.

So, what can we make of this contradiction?

Clearly households are not benefiting from this kind of pick up in economic growth.

Confidence is one factor. According to anecdotal reports, there might be some lingering unease after the covid lockdowns. While there is generally a sentiment that covid lockdowns are a thing of the past, when it comes to people’s actions, that is not the case.

It isn’t surprising given that people in China would have endured strict lockdowns and perhaps months without an income source. Unlike elsewhere in the world, households in Mainland China didn’t get the big fiscal handouts to help them through the pandemic. Naturally, most people in that situation might feel the need buff up their savings – just in case.

And on top of any lingering caution after the pandemic, there is a downturn in the housing market and lacklustre share market.

It begs the question, where is economic growth coming from?

We don’t get the same breakdown in China’s data as in other major economies. But we can glean some insights from other data.

The housing market downturn has meant that residential construction is still dragging on growth rather than adding to it.

Focus from media commentary has been on industrial output, which grew 6.1% on the first quarter a year ago. It is in step with the perceived “quality growth” that authorities are looking for.

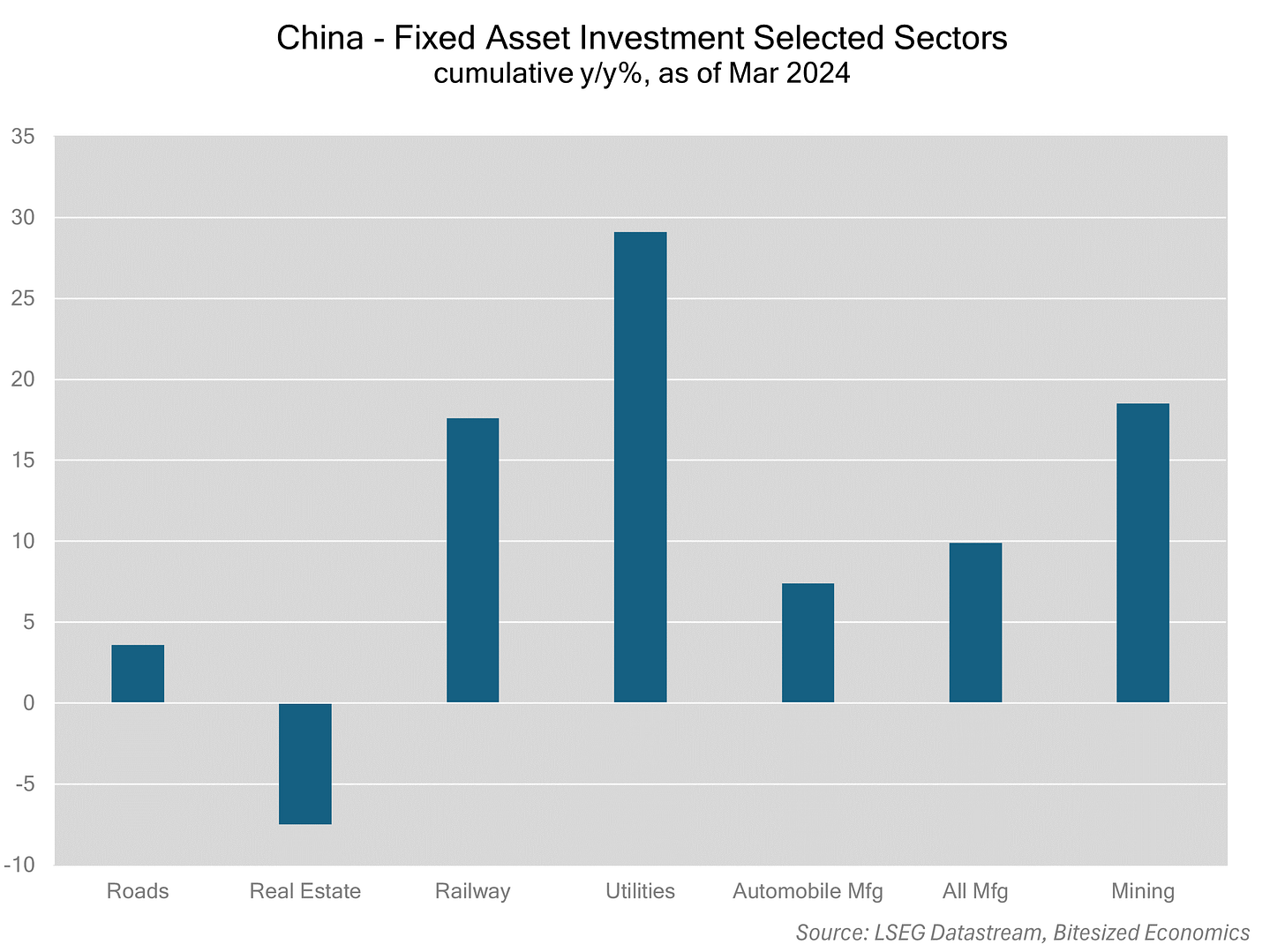

But solid growth investment in fixed assets suggests that investment is still playing a large part in driving economic growth. And this is despite weaker investment in real estate amid the housing downturn. We see strong growth in infrastructure, but more utilities, likely linked to a transition towards green energy. There is firm growth in mining and manufacturing investment. And while there has been less emphasis from policy officials highlighting infrastructure spending, there does appear to be still a fair amount of growth in spending on railways and power stations.

This is nothing new in China’s economy. China has been relying on investment to drive economic growth for decades. It’s just that the mix of investment has shifted away from property to elsewhere. It has been a long-running feature of China’s economy that investment has taken up a disproportionately large proportion of GDP, at over 40% of GDP.

Conversely, consumption has taken up a relatively small proportion of GDP, mostly in the last 20 years. There have also been various calls over the years to shift growth to consumption, including the IMF and academics as well as experts in Chinese policy making.

So why hasn’t this happened?

Some commentators have suggested that there is an opposition to “welfarism”, after President Xi criticized high welfare spending in 2021. But there might be a simpler reason for not providing more direct support to households.

It could be because they never had to.

Throughout the 80s, China has managed to pass on benefits in the growth of its manufacturing sector to households by employing its wide pool of low-cost labour. Subsequently, rising wages and a rapidly expanding property market also added to wealth and incomes of households.

This time around, it appears there is hope that the investment push through advanced technologies, AI and green energy will eventually flow on to households.

In theory, productivity gains from technology should lead to stronger growth in incomes. But those benefits may not be felt for some time, especially to households. And this is really a phenomenon witnessed worldwide and throughout history. For example, the push for industrial robotics in the use of manufacturing reduces the need for as many workers and boosts productivity, but those income gains from wages would have otherwise transferred to households. In the case of AI, while there are potentially enormous, long-run gains in productivity, there is also the likelihood of large-scale displacement of workers in the near-term.

It means that we may not see any flow through effect to households for some time.

Nonetheless, the first quarter data highlights that there is a strong commitment to the growth target, which has included spending on things like infrastructure and supporting production. And despite concerns coming from leaders US and European leaders about overproduction, it is the spending on infrastructure which continues to be an important driver of growth. That explains that despite the ongoing weakness in the housing market, there has been a pickup in Chinese steel production in the first two months of this year, albeit from a low base. Meanwhile, cement production continues to weaken.

Of course, further spending in unproductive investment would exacerbate high debt burdens and continues the path of unbalanced growth. But with the growth target a priority, investment spending still appears to be the key means to get there.

The big question is, if there fails to be much flow on effect to household spending, which may become more apparent later this year, would that be enough to encourage a shift towards policies to support other parts of the economy, including household sector?

The rise of the manufacturing sector and the growth of the property sector led to major gains in incomes and wealth to households. For now, the hope is that an advanced manufacturing push will lead to the same.

Investment Implications

Signs of China’s growth target commitment suggests investors could be underestimating the extent of commodity demand for this year. While there may be ongoing sluggishness in the housing market and consumer spending, investment spending will likely continue to be the means to get there. This would support commodities, and commodity-linked currencies, such as the AUD. There could be good value in shares of diversified miners, particularly given their underperformance over the past year.

********************************************************************************************************

If you want to receive updates, straight to your inbox, please subscribe. And to show additional support I would be extremely thankful if you become a paid subscriber:

Alternatively, you can provide a one-off donation through my buymeacoffee link.

https://buymeacoffee.com/januchanD

All contributions are much appreciated! Thank you to all who have subscribed, shared and donated.