The rise and rise of US employment

A big thank you to all those who have donated, and a very special thank you to those of you who are contributing through a paid subscription. The content on Bitesized Economics is free for now, but any financial contribution is especially appreciated. Otherwise please do continue enjoy - sharing and free subscriptions are also great support. And if you haven’t subscribed, you can do so below:

Or you can provide a one-off donation through the link: https://buymeacoffee.com/januchanD

***********************************************************************************************

One of the major developments in financial markets has been the rise in bond yields. US 10-year yields rose to their highest since 2007, while 30-year yields hit their highest since 2011 last week.

Why does this matter?

It’s because US bond yields affect all kinds of interest rates in the economy, and also around the world. It hasn’t just been US yields which have risen, bond yields in other advanced economies have also lifted to multi-year highs as they tend to track what happens to US yields. Bond yields help determine borrowing rates in the economy, including US mortgage rates and corporate borrowing rates.

Of course, bond yields have been on the way up ever since the global economy recovered from the pandemic and inflation emerged.

There’s no shortage of explanations for the reasons behind the surge in yields – rising issuance of US treasury debt for government spending, persistent inflation and a hotter-than-expected US economy.

However, the jump in recent weeks can likely be attributed to a major re-assessment by financial markets on expectations of Fed interest rates – that interest rates will stay higher for longer.

Financial markets have woken up to the fact that you can’t have a strong economy with rapidly falling inflation at the same time. The odds of a soft-landing may have increased, but that would mean a slower return to 2% inflation and interest rates higher for longer.

But the sudden rise in yields might also reflect a realisation of just how resilient the US economy has been. If anything, economic indicators have pointed to a pickup in the US economy since the middle of 2023.

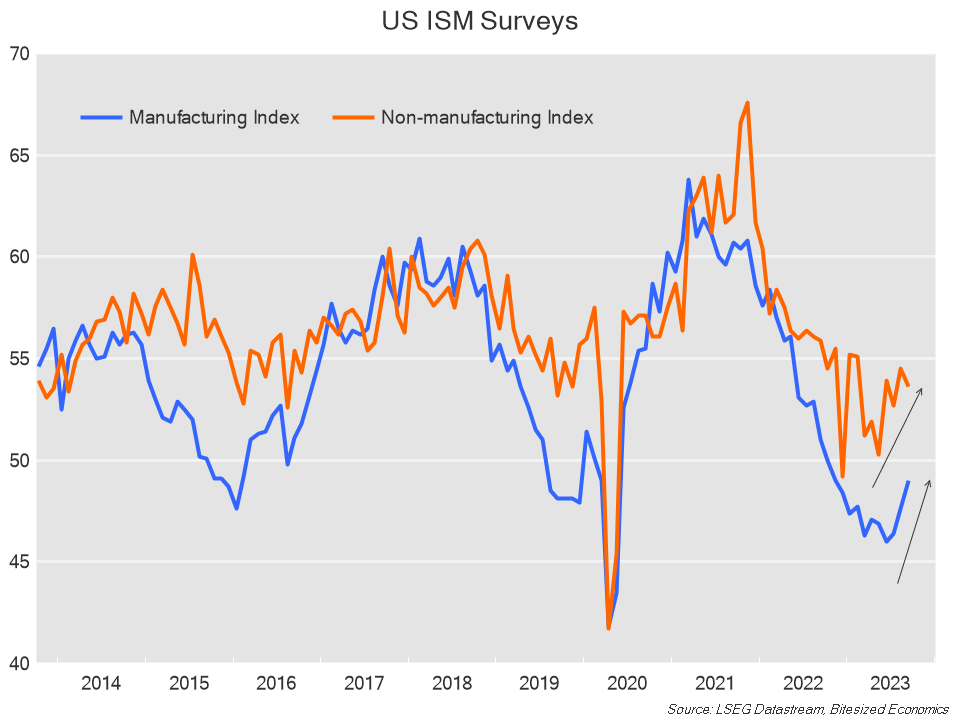

Here are indices from ISM surveys which measure manufacturing and services activity in the US:

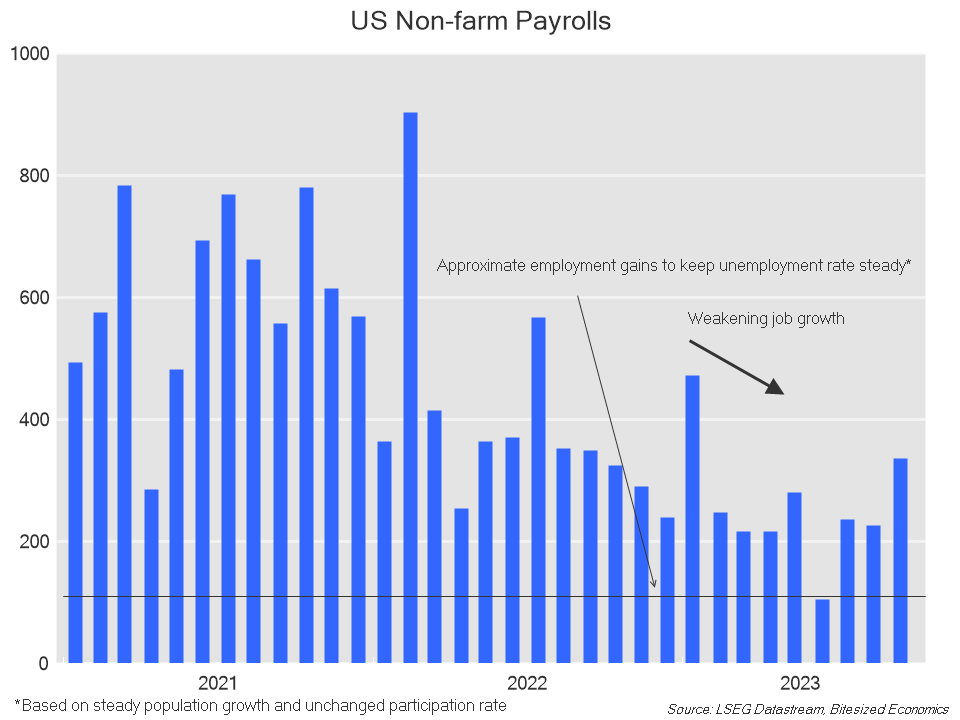

Importantly, the labour market is also continuing to show signs of strength. Although some indicators point to some moderation in employment, we’re still not seeing enough signs that jobs will weaken enough to have confidence we will see a sustained rise in the unemployment rate:

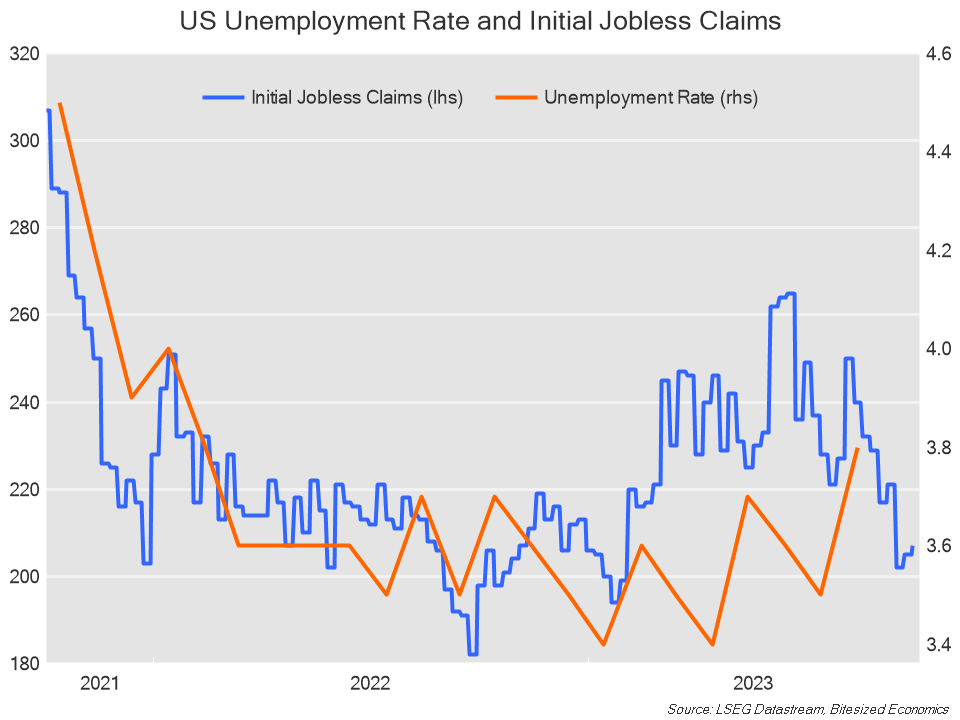

Jobless claims have even fallen:

Based on recent economic indicators, it would seem as though the economy is weathering interest rate hikes very well.

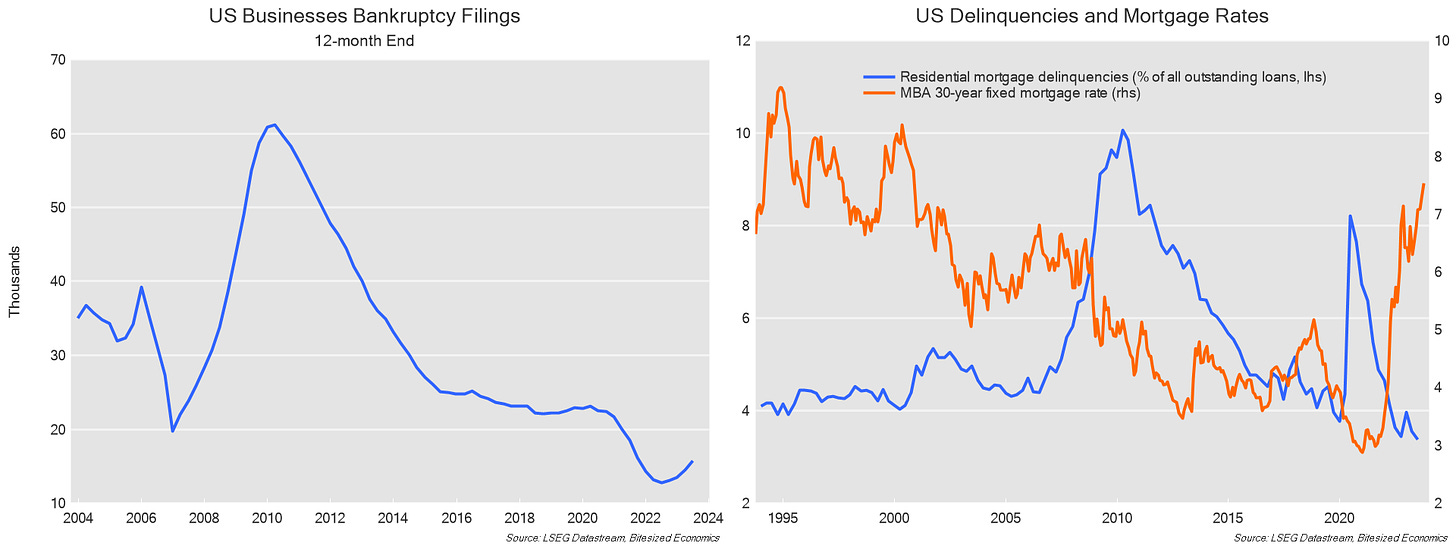

There is also little sign of financial distress among businesses and households.

Corporate insolvencies have been on the rise, but remain very low, and well below pre-pandemic levels. Delinquencies on mortgages are also extremely low:

It is somewhat surprising that the US economy can be this resilient with a fed funds rate at above 5% and US 10 and 30-year bonds yielding above 4.6%.

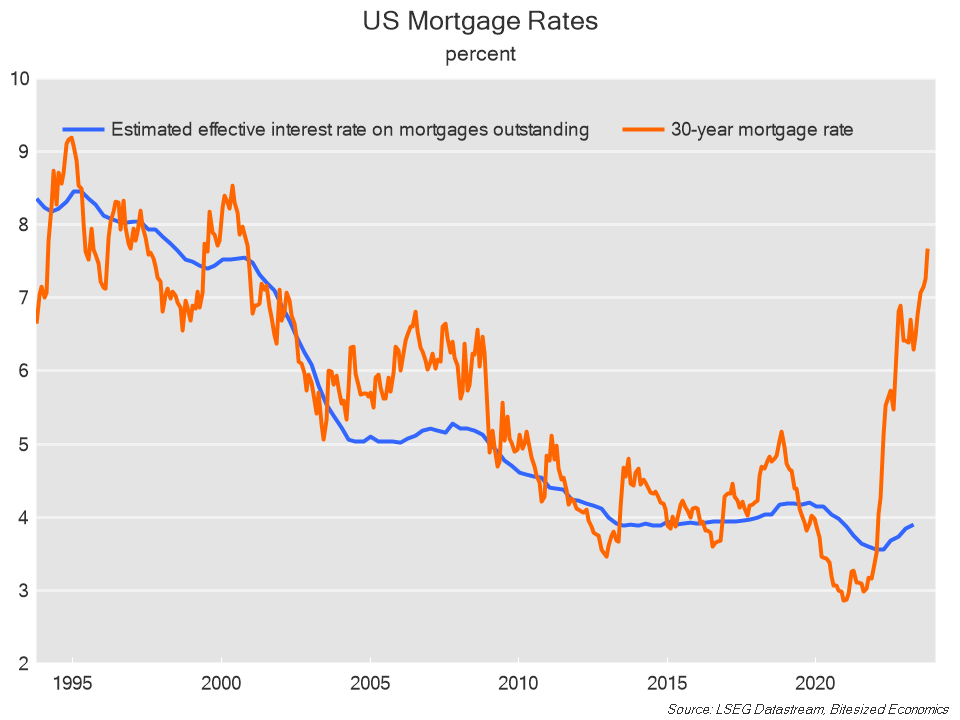

One valid explanation for the muted response in the economy to rising interest rates is that there hasn’t been enough time for tighter Fed policy to flow through to actual borrowing rates in the economy. The majority of mortgage holders are on long-term fixed rates (up to 30 years), so households may not face the pressure from higher interest rates on their budgets for some time. The Fed estimates more than 90 percent of mortgages are on long-term fixed rates.

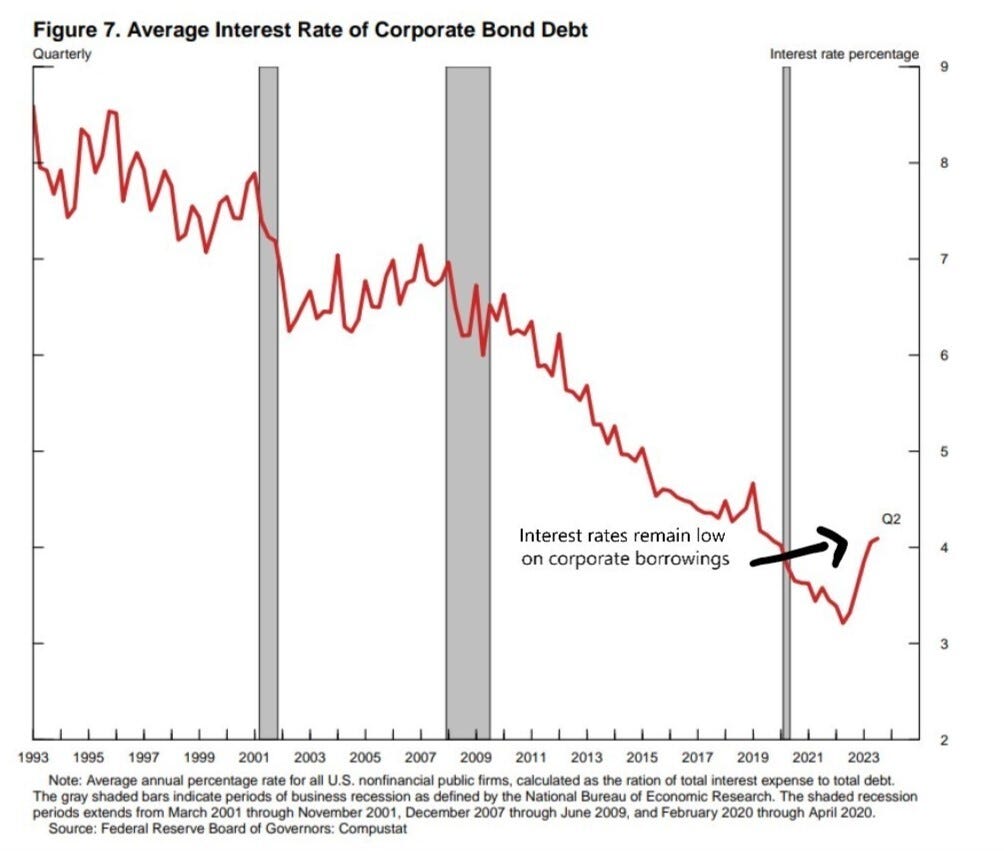

Corporates also predominantly use fixed-rate debt for their borrowings through corporate debt, so average interest rates have further to increase once these bonds need refinancing.

What this means is that the borrowing rates which affect the economy depend on not just current policy rates but whatever policy rates were years ago. So, the legacy of rock-bottom levels during the pandemic is helping to keep borrowing rates lower than would be implied by current levels of the Fed funds rate and bond yields. This is what Fed Chair Powell refers to when he speaks of the lag impact of monetary policy. It means it might take a while, years even, for higher policy rates to take effect in bringing down demand in the economy.

It provides some explanation for why higher interest rates are not affecting the US as much as other parts of the world. For example, banks play a relatively larger role in financing corporates in Europe, as opposed to bonds, and therefore more exposed to short-term interest rates or in Australia where the majority of mortgages are on variable rates instead of fixed.

That’s a great argument for the Fed to just leave rates where they are even though the economy continues to show strength over the next few months and just wait for tighter policy to take effect.

But the message from Fed chair Powell that policy decisions would be increasingly “data dependent” suggests that the Fed may not to wait more than a couple of months before determining that even tighter policy would be needed. That increases the chances that policy will end up being restrictive than necessary.

Ironically, the shift in expectations and rising bond yields ends up tightening monetary policy for the US Federal Reserve, and so lessens the chance the Fed will need to raise the Fed funds rate more. But that also means that if bond yields retreat, the Fed may be tempted to raise rates again, or at least keep the chances of a rate hike alive.

The strength of the US economy has been astounding and comes despite the now high levels of interest rates. There is a possibility that the US economy might just be way more resilient to higher interest rates than expected. But it might just be that it will take more time for higher interest rates to dampen the economy. If so, the risk of a hard landing hasn’t decreased – it’s just been shifted out to 2024.